Introduction

On Aug. 11, 2000, President Clinton signed Executive Order 13166: Improving Access to Service for persons with Limited English Proficiency, to clarify Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The executive order was issued to ensure accessibility to programs and services to otherwise eligible individuals not proficient in the English language.

The executive order stated that individuals with a limited ability to read, write, speak, and understand English are entitled to language assistance under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with respect to a particular type of service, benefit, or encounter. These individuals are referred to as being limited in their ability to speak, read, write, or understand English, hence the designation, “LEP,” or Limited English Proficient.

The USDOT published “Policy Guidance Concerning Recipients’ Responsibilities to Limited English Proficiency” in the Dec. 14, 2005, Federal Register. The guidance explicitly identifies state agencies such as the Agency of Transportation (AOT) as organizations required to follow Executive Order 13166.

The guidance applies to all DOT funding recipients, which include state departments of transportation, state motor vehicle administrations, airport operators, metropolitan planning organizations, and regional, state, and local transit operators, among many others. Coverage extends to a recipient’s entire program or activity; i.e., to all parts of a recipient’s operations.

To meet Title VI and LEP requirements, the AOT will evaluate, on a continuing basis, activities that would be appropriate for compliance with LEP requirements.

A. Four Factor Analysis

The DOT guidance outlines four factors’ recipients should apply to the various kinds of contacts they have with the public to assess language needs and decide what reasonable steps they should take to ensure meaningful access for LEP persons:

- The number and proportion of LEP persons eligible to be served or likely to be encountered by a program, activity, or service of the recipient or grantee.

- The frequency with which LEP persons come in contact with the program.

- The nature and importance of the program, activity, or service provided by the recipient to the LEP community.

- The resources available to the AOT and overall cost.

Factor 1 – Prevalence of LEP Persons

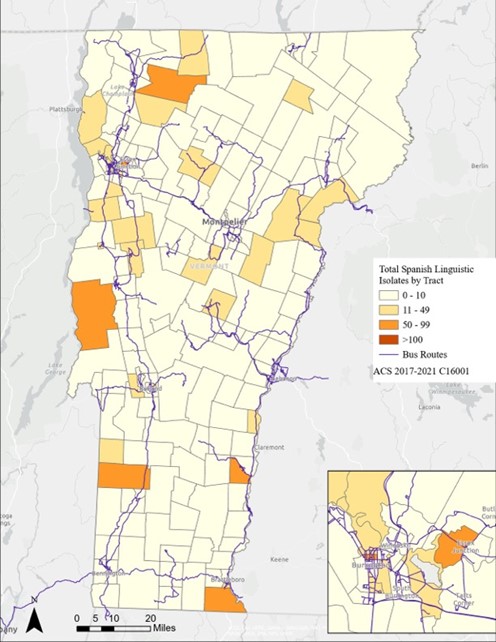

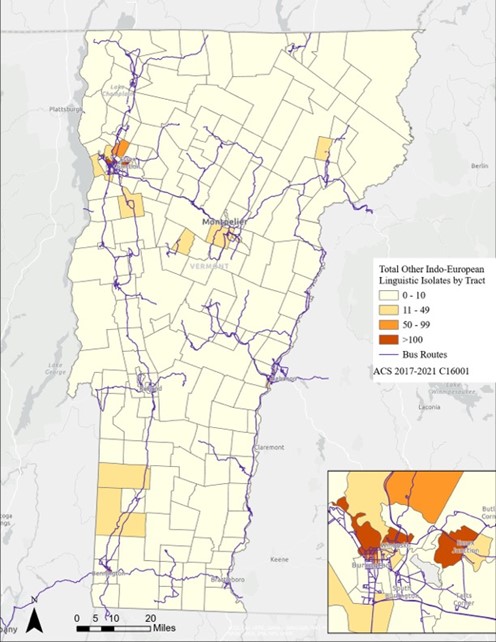

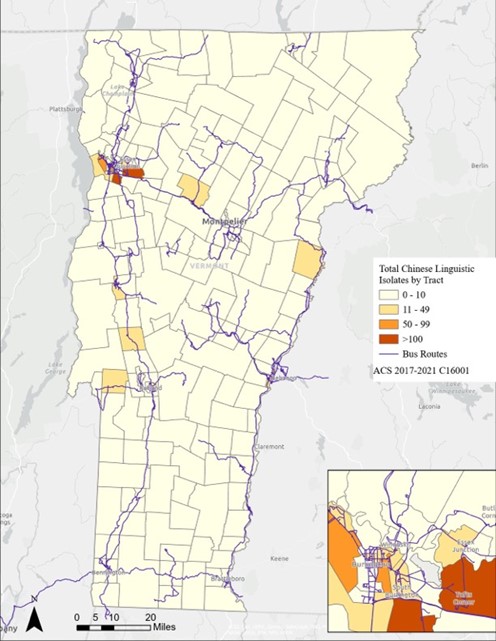

According to the 2017-2021 American Community Survey, 7,705 residents of the state of Vermont ages 5 or older spoke English less than very well, representing 1.26% of the population. The largest language-group was French with 1,570 individuals, reflecting French-Canadians who are most-commonly represented in rural areas across the northern tier of Vermont. Other Indic Language speakers were the second largest group, with 1,205 individuals, reflecting the large influx of Bhutanese refugees into the Burlington metropolitan area over the past 15 years. Spanish speakers were the third largest group, with 1,200 individuals. Many of the Spanish speakers are migrant farm workers in the rural areas of the state. The only other language group with more than 500 individuals is Chinese, with 737. Maps presented below show the number and percentages by tract for all languages combined, and then by tract for each of the top four languages. Other efforts to identify English Language Learners (ELLs) besides the use of Census data are described below.

Within the realm of public transportation, the AOT interacts with the public in two primary ways. In terms of direct experience, the AOT may come in contact with ELLs at public meetings or public hearings associated with planning efforts. The AOT has two primary periodic planning efforts wholly within or related to public transportation that entail public review and comment:

- Long Range Transportation Business Plan

- Public Transit Policy Plan/Human Service Transportation Coordination Plan

At public meetings for these projects, it is incumbent upon the AOT to provide a means for all to participate in a meaningful way. In advertising the meetings, the AOT indicates that translation services are available upon request. For projects located in an area with a higher prevalence of ELLs—central Chittenden County— the AOT and the Chittenden County Regional Planning Commission (CCRPC) (if applicable) also collaborate with community organizations representing immigrant populations to encourage participation and facilitate communication.

The other primary form of interaction of individuals with ELLs with the AOT is through subrecipients. The seven public transit providers in Vermont have more direct contact with ELLs than the AOT, though the degree of interaction varies across the state. It is the responsibility of the providers—which include one transit authority, one transit district, and five private non-profit agencies—to deploy the resources necessary to ensure that ELLs have fair access to the available services. However, it is the AOT’s responsibility as the FTA grant recipient to monitor the efforts of the providers and ensure compliance with Executive Order 13166.

The forms of interaction with ELLs experienced by the transit providers include the following:

- Providing basic information on how to use public transit services in the area

- Purchasing fare media

- Making reservations on demand-response services such as ADA paratransit, Older Persons and Persons with Disabilities transportation, and general public dial-a-ride

- Handling passenger complaints

- Gathering data such as on-board customer surveys.

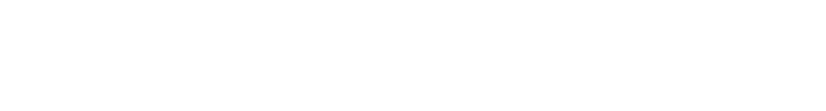

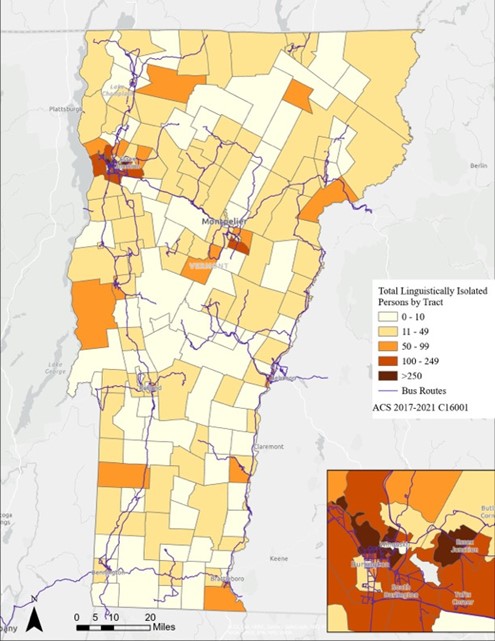

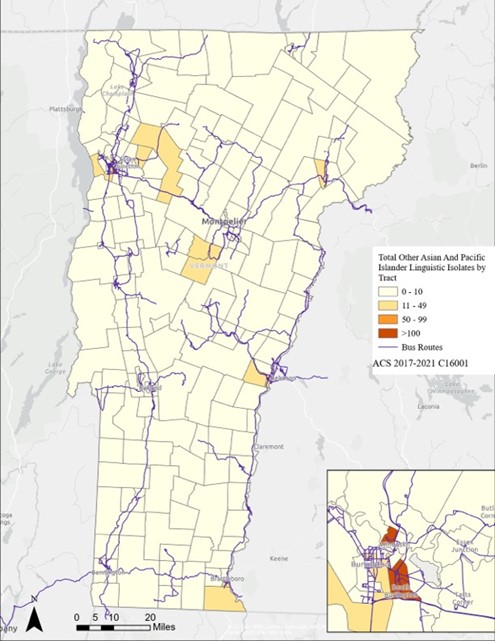

The maps below illustrate where linguistically isolated persons reside in Vermont. The maps use Census tracts and are based on 2017-2021 American Community Survey data at the tract level. The first map shows the number of individuals by tract who speak English “less than very well.” In 35 of the 192 Census tracts in Vermont, there are zero people who are “linguistically isolated” (i.e., speaking English less than very well). In another 37 tracts, there are between 1 and 10 linguistically isolated individuals. The LEP guidance from DOT indicates lower requirements for recipients that serve “very few” LEP individuals; the Safe Harbor provision in FTA Circular C 4702.1B (page III - 9) indicates 50 individuals is the threshold for reduced requirements. In total, 154 of Vermont’s 192 tracts (80%) have fewer than 50 linguistically isolated persons. There were only eight tracts with 200 or more linguistically isolated persons; all of these were in Chittenden County. The second map below shows tracts where the percentage of linguistically isolated persons is higher than the 2017-2021 statewide average of 1.26%; i.e., “concentrations” of linguistically isolated individuals.

It is clear from the data, as well as from the experience of the transit providers, that LEP are not widespread in Vermont. Outside of the core of Chittenden County, there are only two tracts where there are 100 or more people who don’t speak English very well: one in Barre Town and one in the center of Bennington. Note that the Census data do not reflect recent influxes of refugees from Afghanistan (2021-2022) or Ukraine (2022-2023).

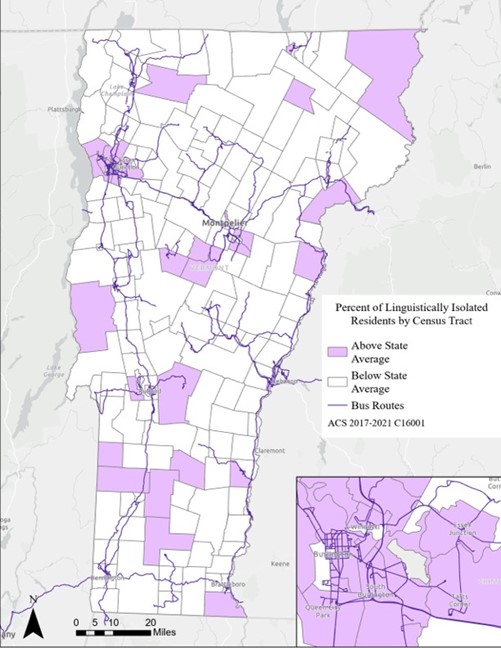

The next step in the analysis was to consider specific language groups and where there are concentrations of individuals who do not speak English well. In the maps above, it can be seen that at the tract level, other than in the core of Chittenden County, the numbers of people who do not speak English well are small. When these groups are broken down further into specific languages, the numbers become even smaller.

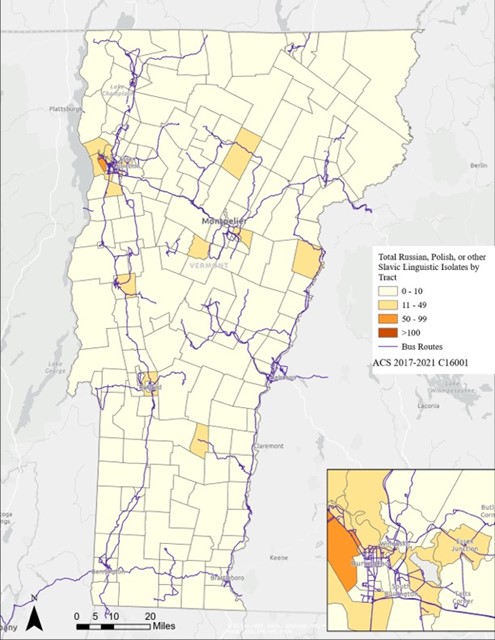

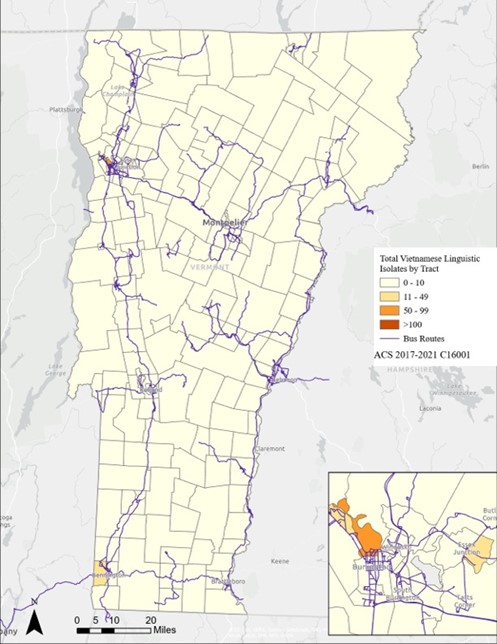

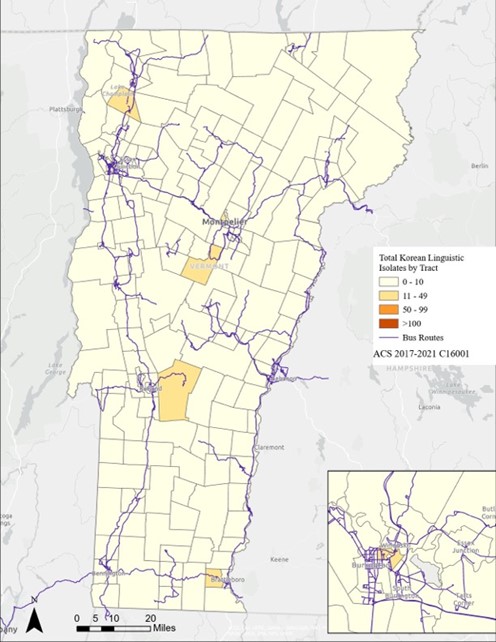

The maps display the number of persons who speak English “less than very well” and whose primary language is French, Spanish, Other Indo-European Languages, Chinese, Other Asian and Pacific Islander (primarily Burmese), Russian/Polish/Slavic, Vietnamese, and Korean. Statewide, these are the only languages (besides “Other and Unspecified”) that have more than 100 individuals who speak English less than very well.

On the French language map (1,619 total linguistic isolates), the highest numbers of linguistic isolates are in the center of Chittenden County and Barre Town. A pattern in prior Title VI patterns of a high incidence of French speakers among the northern tier has dissipated to some extent, as these tracts in northern Essex County and Orleans County now have between 20 and 35 linguistic isolates whereas in previous data sets had more than 40. This trend could represent older residents with ties to Quebec passing on in the intervening years. The higher numbers in Barre and the Burlington area likely reflect recent immigration from Haiti rather than legacy ties to Quebec. Indeed, the highest absolute numbers and highest percentages of French speakers are in the South End of Burlington, the southern part of Barre Town and the eastern part of South Burlington.

Compared to prior Census data, individuals who speak Spanish are spread over a wider area with fewer concentrations. In 2015, there were three tracts with percentages well over 2 percent, but in the current data, only Tract 104 in Franklin County crosses that threshold at 2.07%. The highest absolute number in any tract is 72, in the Old North End of Burlington. Concentrations in prior analyses were attributed to migrant farm workers. It is possible that there were fewer such farm workers during the pandemic.

Other Indo-European Languages, spoken by 1,748 linguistically isolated individuals, mostly comprises Nepali, Marathi, or other Indic languages (1,205 of the 1,748) reflecting the many refugees from Bhutan that settled in Chittenden County from 2008 to 2017 (see Factor 2 below). The great majority of these individuals are located in the core of Chittenden County, in Winooski, the western part of Essex Junction and the Intervale neighborhood of Burlington. The percentages of total population in these tracts range from 3.7% in the Intervale to 11.4% in the western part of Winooski. The central part of Bennington has 103 linguistic isolates in this language group (2.45% of the population), but the Census data do not provide more detailed information on which specific language is spoken by these individuals.

On the Chinese language map (737 total linguistic isolates), it can be seen that linguistically isolated Chinese speakers are clustered almost exclusively in tracts in Chittenden County. Earlier data sets showed a wider distribution. The highest concentrations are in the Route 116 corridor in South Burlington, the northern part of Williston, and the portion of Burlington containing UVM.

Other Asian and Pacific Islander languages reflect primarily Burmese refugees who have settled in Chittenden County. There are scattered other tracts in St. Johnsbury, Hartford, Guilford, and Northfield where there are clusters of speakers of these languages.

Speakers of Slavic languages also reflect an influx of refugees, this time Bosnians who speak Serbo-Croatian and arrived in Chittenden County more than a decade ago. There are other tracts as well, including Middlebury, Rutland, Northfield, Barre, and Newbury, among others.

Vietnamese and Korean have relatively fewer speakers in Vermont, with fewer than 200 speaking English less than very well. Vietnamese speakers are almost exclusively in the New North End of Burlington, as well as some in Essex Junction. Tracts with Korean speakers are spread over the state, with no significant clusters visible.

Information about all other languages spoken in Vermont is shown on the following the maps. This information, as well as the data for the maps, is drawn from the 2017-2021 American Community Survey from the US Census.

It can be seen that within any tract, no language group surpasses 400 individuals, however, there are three tracts in Chittenden County where linguistic isolates in one language surpass 5% of the population. These cases involve refugees from Bhutan and Burma in Tract 24, and additional Bhutanese refugees in Tract 25.01 and Tract 26.01. Green Mountain Transit (GMT) has engaged in direct outreach to these populations, assisted by the US Committee on Refugees and Immigrants – Vermont (formerly Vermont Refugee Resettlement Program). The Title VI Program of the Chittenden County Regional Planning Commission (CCRPC), the metropolitan planning organization for the urbanized area, also covers these concentrations of linguistically isolated individuals.

At the statewide level, French, Nepali and Spanish have more than 1,000 individuals, but as stated above, the French speakers are spread across the entire northern tier of the state with some newer concentrations in Chittenden County, and Spanish speakers are spread among many tracts. Refugees from Bhutan who speak Nepali are more concentrated and outreach activities in the central part of Chittenden County should always include outreach and accommodation of this population.

On the occasions when the AOT holds public meetings on statewide projects, it offers translation services upon request. It would not be an effective use of resources to prepare all vital documents in Spanish and French without a direct request to do so from one or more individuals. If, in the future, there are requests for statewide documents to be translated into French or Spanish (or other languages), the AOT will honor those requests either by providing the written translation or contacting those individuals to provide oral translation services to answer their questions.

Factor 2 – Frequency of Contact with LEP Persons

As indicated in discussion of Factor 1, the AOT is most likely to have direct contact with ELLs at public meetings associated with public transportation planning efforts. The AOT operates no transit service. The AOT staff does handle occasional phone calls and e-mails from the public for its van pool / ride share program, Go Vermont, though its contractor, Commute with Enterprise, handles most of the public interaction. Though in ten years there have been no people calling in to use this service, on-call translation via telephone is available if anyone should do so.

Factor 3 – Importance to LEP Persons of Program, Activities and Services

Many ELLs, at least in the short term, rely on public transportation for mobility. The seven public transit providers are responsible for ensuring that people are not hindered from using local transit systems because of the inability to speak English well. The AOT must ensure through its oversight activities that the providers are upholding this responsibility.

In addition, as the state transportation agency responsible for coordinating the statewide transportation planning process, the AOT must make sure that all segments of the population, including ELLs, have the opportunity to be involved with the planning process. The impact of proposed transportation investments on underserved and underrepresented population groups is part of the evaluation process. The AOT provides oversight and ensures in its own planning projects that ELLs and other protected classes of persons are not overlooked.

In its ongoing communication with organizations representing immigrant and low-income populations, the AOT will make sure that the state and its subrecipients are carrying out these language access responsibilities effectively. Within state government, the State Refugee Office within the Agency of Human Services coordinates relief and resettlement efforts. It works with the US Committee on Refugees and Immigrants, the Ethiopian Community Development Council and the Association of Africans Living in Vermont, three nonprofit agencies working to support refugees in Vermont.

Factor 4 – Resources Available and Cost

Because of the very low incidence of ELLs in Vermont overall, the cost to accommodate them has not been burdensome. The AOT provides in-person and telephone translation services for all the AOT activities and the AOT subrecipients. It is not foreseen that the resources available or the cost of translation services will hinder the accommodation of the needs of Vermont’s ELLs populations. The transit providers were explicitly added to the Telelanguage (Now Propio Language Services) contract in June of 2017. Each provider was assigned a department code number and given instructions on how to use the service. See the AOT Civil Rights Office webpage for more information.

B. Providing Language Assistance

The AOT provides oral and written translation; written interpretation and translation; and sign language, as requested, or as a result of a demographic analysis of ELLs on any given project or projected program. The AOT will continue to examine its services and survey its employees and subrecipients to determine the extent of contact or the possibility of contact with ELLs as needed.

The State’s Office of Racial Equity has published the 2023 Language Access Report, with more information and recommendations for making all state services accessible to individuals no matter their ability to speak and read English.

C. Providing Notice to LEP Persons

After ELL populations have been identified, strategies are developed to provide notice of a program, service, or activity, using appropriate media, including brochures (also in languages other than English). Community groups serving ELL populations are contacted, as well as schools, church groups, chambers of commerce, and other relevant entities.

D. Monitoring, Evaluating and Updating the Language Access Policy (LAP)

Through monitoring news reports and communication with the State Refugee Office, the AOT stays abreast of changes in the composition of language access needs in Vermont. Of course, the update of this Title VI Program every three years necessitates the downloading of new data from the Census, which also indicates any new populations which may face language barriers. The AOT also works closely with its subrecipients, which have more direct interactions with immigrants, to update its information regarding needs of ELLs.

E. Training Staff and Others

All the AOT staff involved in public outreach and public involvement receive training on identifying ELL populations and providing translation and interpretation services. Subrecipients and the CCRPC must provide these services to be in compliance with Title VI and Executive Order 12898. Subrecipient reviews are conducted to ensure compliance with this executive order.

Oversight of Subrecipients’ LEP Programs

Each of the transit providers which are subrecipients of FTA funds has an LEP plan in place as part of its Title VI Program. The AOT requires that all subrecipients submit a Title VI Program at least every three years, and these programs must contain an LAP that is compliant with federal regulations. The validity of the LAP is part of the triennial reviews that the AOT conducts. The transit providers track interactions with ELLs that result in not addressing the needs of that individual, whether it occurred in the field (on the bus) or in the course of contact with office staff (i.e., a reservation specialist or a front-desk employee answering questions in person or on the phone). The providers will also be responsible for maintaining contact with local organizations that represent immigrant populations to stay abreast of changes in the mix of languages in their service areas.

As of 2023, GMT is the most likely agency to come into contact ELLs, and its procedures are discussed in more detail in its Title VI program. SEVT’s MOOver system publishes its “How to Ride” guides in Spanish, Pashto and Dari and the agency does direct outreach and travel training for refugees, mainly from Afghanistan, in the Brattleboro area in coordination with the Ethiopian Community Development Council. Winter seasonal staff at Mount Snow for the MOOver are able to communicate in Spanish. RCT has periodically published its schedule book in French.

Resources, language service providers and point-to-your-language poster are available via the AOT Civil Rights Office webpage.